.NET Core 3.0 Intrinsics in Real Life - (Part 1/3)

I’ve recently overhauled an internal data structure we use at Work® to start using platform dependent intrinsics- the anticipated feature (for speed junkies like me, that is) which was released in preview form as part of CoreCLR 2.1: What follows is sort of a travel log of what I did and how the new CoreCLR functionality fares compared to writing C++ code, when processor intrinsics are involved.

This series will contain 3 parts:

- The data-structure/operation that we’ll optimize and basic usage of intrinsics (this post).

- Using intrinsics more effectively.

- The C++ version(s) of the corresponding C# code, and what I learned from them.

All of the code (C# & C++) is published under the bitgoo github repo, with build/run scripts in case someone wants to play with it and/or use it as a starting point for humiliating me with better versions.

In order to keep people motivated:

- By the end of this post, we’ll already start using intrinsics, and see considerable speedup in our execution time

- By the end of the 2nd post, we will already see a 300% speed-up compared to my current .NET Core 2.1 production code, and:

- By the end of the 3rd post I hope to show how with some fixing in the JIT, we can probably get another 100%-ish improvement on top of that, bringing us practically to C++ territory1

The What/Why of Intrinsics

Processor intrinsics are a way to directly embed specific CPU instructions via special, fake method calls that the JIT replaces at code-generation time. Many of these instructions are considered exotic, and normal language syntax cannot map them cleanly.

The general rule is that a single intrinsic “function” becomes a single CPU instruction.

Intrinsics are not really new to the CLR, and staples of .NET rely on having them around. For example, practically all of the methods in the Interlocked class in System.Threading are essentially intrinsics, even if not referred to as such in the documentation. The same holds true for a vast set of vectorized mathematical operations exposed through the types in System.Numerics.

The recent, new effort to introduce more intrinsics in CoreCLR tries to provide additional processor specific intrinsics that deal with a wide range of interesting operations from sped-up cryptographic functions, random number generation to fused mathematical operations and various CPU/cache synchronization primitives.

Unlike the previous cases mentioned, the new intrinsic wrappers in .NET Core don’t shy away from providing model and architecture specific intrinsics, even in cases were only a small portion of actual CPUs might support them. In addition, a .IsHardwareAccelerated property was sprinkled all over the BCL classes providing intrinsics to allow runtime discovery of what the CPU supports.

On the performance/latency side, which is the focus of this series, we often find that intrinsics can replace tens of CPU instructions with one or two while possibly also eliminating branches (sometimes, more important than using less instructions…). This is compounded by the fact that the simplified instruction stream makes it possible for a modern CPU to “see” the dependencies between instructions (or lack thereof!) more clearly, and safely attempt to run multiple instructions in parallel even inside a single CPU core.

While there are some downsides as well to using intrinsics, I’ll discuss some of those at the end of the second post; by then, I hope my warnings will fall on more welcoming ears.

Personally, I’m more than ready to take that plunge, so with that long preamble out of the way, let’s describe our starting point:

The Bitmap, GetNthBitOffset()

To keep it short, I’m purposely going to completely ignore the context the code we are about to discuss is a key part of (If there is interest, I may write a separate post about it). For now, let’s accept that we have a god-given assignment in the form of a function that we really want to optimize the hell out of, without stopping to ask “Why?”.

The Bitmap

This is dead simple: we have a bitmap which is potentially thousands or tens of thousands of bits long, which we will store somewhere as an ulong[]:

1

2

const int THIS_MANY_BITS = 66666;

ulong[] bits = new ulong[(THIS_MANY_BITS / 64) + 1]; // enough room for everyone

The bits array in the sample above is continuously being mutated, and as bits go, this is going to be in the form of bits being turned on and off in no particular order, so imagine:

1

2

3

var r = new Random(DateTime.Ticks % int.MaxValue);

for (var i = 0; i < bits.Length; i++)

bits[i] = unchecked(((ulong)r.Next()) << 32 | ((ulong) r.Next()));

The Search Method

We’re about to describe one of the two methods that I optimized. I chose this particular method since it was the more challenging one to optimize. But before describing it, a short disclaimer is in order:

The method is implemented with unsafe and ulong * rather than the managed/safe variants (ulong[] or Span<ulong>). The reasons I’m using unsafe are that for this type of code, which makes up double digit % of our CPU time, adding bounds-checking can be very destructive for performance; Specifically, in the context of this series where I’m about to compare C# with C++, we get an apples-to-apples comparison, as C++ is compiled without bounds-checking normally.

With that out of the way, lets inspect the method signature:

1

unsafe int GetNthBitOffset(ulong *bits, int numBits, int n);

This method runs over the entire bitmap until it finds the nth bit with the value 1, or as I will refer to it here-on, our target-bit, and returns its bit offset within the bitmap as its return value.

For brevity we assume that incoming values of n are never below 1 or above the number of 1 bits in the bitmap.

Here’s a super naive implementation that achieves this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

public static unsafe int Naive(ulong* bits, int numBits, int n)

{

var b = 0;

var value = *bits;

var leftInULong = 64;

var i = 0;

while (i < numBits) {

if ((value & 0x1UL) == 0x1UL)

i++;

if (i == n)

break;

value >>= 1;

leftInULong--;

b++;

if (leftInULong != 0) // Still more bits left in this ulong?

continue;

value = *(++bits); // Load a new 64 bit value

leftInULong = 64;

}

return b;

}

Initial Performance

This implementation is obviously pretty bad, performance wise. But wait: There are lots of ways you could improve upon this: bit-twiddling hacks, LUTs and what we’re here for, processor intrinsics.

Our next step is to start measuring this, and we’ll move on to better and better versions of this method, until we exhaust my abilities to make this go any faster.

Using everyone’s favorite CLR microbenchmarking tool, BDN, I wrote a small harness that preallocates a huge array of bits, fills it up with random values (roughly 50% 0/1), then executes the benchmark(s) over this array looking for all the offsets of lit bits up to N where N is parametrized to be: 1, 8, 64, 512, 2048, 4096, 16384, 65536.

The benchmark code looks roughly like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

const int KB = 1024;

[Params(1, 4, 16, 64, 256, 1*KB, 4*KB, 16*KB, 64*KB)]

public int N { get; set; }

protected unsafe ulong *_bits;

...

[Benchmark]

public unsafe int Naive()

{

int sum = 0;

for (var i = 1; i <= N; i++)

sum += GetNthBitOffset.Naive(_bits, N, i);

return sum;

}

For those in the know, I’m NOT using BDN’s OperationsPerInvoke() to normalize for N since the benchmark is looping over the entire bitmap, and the performance varies wildly throughout the loop.

Running this gives us the following results:

| Method | N | Mean (ns) |

|---|---|---|

| Naive | 1 | 1.185 |

| Naive | 4 | 35.308 |

| Naive | 16 | 605.021 |

| Naive | 64 | 6,368.355 |

| Naive | 256 | 99,448.636 |

| Naive | 1024 | 2,057,984.353 |

| Naive | 4096 | 68,728,413.667 |

| Naive | 16384 | 1,365,698,984.333 |

| Naive | 65536 | 22,669,217,647.333 |

A couple of comments about these results:

- Small numbers of bits actually work out OK-ish given how bad the code is.

- Yes, finding all the offsets of the first 64k lit bits (so 64K calls times average length of 64K bits processed per call2) takes a whopping 22+ seconds…

Prepping the Machine / CLR + Environmental information

Here is the BDN environmental data about my machine:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

BenchmarkDotNet=v0.11.0, OS=ubuntu 18.04

Intel Core i7-7700HQ CPU 2.80GHz (Sky Lake), 1 CPU, 4 logical and 4 physical cores

.NET Core SDK=3.0.100-alpha1-20180720-2

[Host] : .NET Core 3.0.0-preview1-26814-05 (CoreCLR 4.6.26814.06, CoreFX 4.6.26814.01), 64bit RyuJIT

ShortRun : .NET Core ? (CoreCLR 4.6.26814.06, CoreFX 4.6.26814.01), 64bit RyuJIT

Job=ShortRun Toolchain=3.0.100-alpha1-20180720-2 IterationCount=3

LaunchCount=1 WarmupCount=3

Keen eyes will notice I’m running this with .NET Core 3.0 pre-alpha / preview. While this is completely uncalled for the code we’ve seen so far, the next variations will actually depend on having .NET Core 3.0 around, so I ran the whole benchmark set with 3.0.

I’m using an excellent prep.sh originally prepared by Alexander Gallego that basically kills the Turbo effect on modern CPUs, by setting up the min/max frequencies to the base clock of the machine (e.g. what you would get when running 100% CPU on all cores).

My laptop has an Intel i7 Skylake processor model 7700HQ with a base frequency of 2.8Ghz, so I ran the following commands on my laptop as root:

1

2

3

4

5

source prep.sh # to get the bash functions used below

cpu_enable_performance_cpupower_state

cpu_set_min_frequencies 2800000

cpu_set_max_frequencies 2800000

cpu_available_frequencies # should print 2800000 for all 4 cores, in my case

This is done so that the numbers presented here are applicable for multi-core machines running this code on all cores, and so that very short benchmarks don’t get skewed results compared to longer benchmarks due to CPU frequency scaling.

PopCount() without POPCNT

Now that we have the initial code out of the way, we’re not going to look at it anymore. The next version will use bit-twiddling hacks in order to count larger groups of bits much faster.

We’ll introduce two pure C# functions that implement population counts:

The Hamming weight of a string is the number of symbols that are different from the zero-symbol of the alphabet used. It is thus equivalent to the Hamming distance from the all-zero string of the same length. For the most typical case, a string of bits, this is the number of 1’s in the string, or the digit sum of the binary representation of a given number and the ℓ₁ norm of a bit vector. In this binary case, it is also called the population count,[1] popcount, sideways sum,[2] or bit summation.[3]

Ultimately, one of the key processor intrinsics we will use is… POPCNT which does exactly this, as a single instruction at the processor level, but for now, we will implement a PopCount() method without those intrinsics, for 64/32 bit inputs.

Apart from PopCount() we will also define a TrailingZeroCount()3 method, that counts trailing zero bits. I chose an implementation that uses PopCount() internally.

Here are the two PopCount() and TrailingZeroCount()methods shamelessly stolen throughout the interwebs from Hacker’s delight:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

public class HackersDelight

{

public static int PopCount(ulong b)

{

b -= (b >> 1) & 0x5555555555555555;

b = (b & 0x3333333333333333) + ((b >> 2) & 0x3333333333333333);

b = (b + (b >> 4)) & 0x0f0f0f0f0f0f0f0f;

return unchecked((int) ((b * 0x0101010101010101) >> 56));

}

public static int PopCount(uint b)

{

b -= (b >> 1) & 0x55555555;

b = (b & 0x33333333) + ((b >> 2) & 0x33333333);

b = (b + (b >> 4)) & 0x0f0f0f0f;

return unchecked((int) ((b * 0x01010101) >> 24));

}

public static int TrailingZeroCount(uint x) => PopCount(~x & (x - 1));

}

These methods can quickly and without a single branch instruction, count the lit bits in 64/32 bit words, with just 12 arithmetic operations, most of them simple bit operations and only one (!) multiplication.

With our bit-twiddling optimized functions implemented and out of the way, let’s put them to good use in a new implementation, and make a few changes in the flow of the code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

using static BitGoo.HackersDelight;

public static unsafe int NoIntrisics(ulong* bits, int numBits, int n)

{

// (1)

var p64 = bits;

int prevN;

do {

prevN = n;

n -= PopCount(*p64);

p64++;

} while (n > 0);

// (2)

var p32 = (uint *) (p64 - 1);

n = prevN - PopCount(*p32);

if (n > 0) {

prevN = n;

p32++;

}

// (3)

var prevValue = *p32;

var pos = (p32 - (uint*) bits) * 32;

while (prevN > 0) {

var bp = TrailingZeroCount(prevValue) + 1;

pos += bp;

prevN--;

prevValue >>= (int) bp;

}

return (int) (pos - 1);

}

Our new approach to solving this goes like this (comments correspond to blocks of the code above):

- As long as we still need to look for any

1bits, we loop, callingPopCount()until we finally consume more bits than what we were tasked with… At that stage ourp64pointer is pointing 1ulongbeyond theulongcontaining our target-bit, andprevNcontains the number of consumed1bits that was still correct oneulongbefore. - Once we’re out of the loop, we know that out target-bit is hiding somewhere within that last 64-bit

ulong. So we will use a single 32-bitPopCount()to figure out if its within the first/second 32-bit words making up that 64-bit word and update the bit-counts /p32pointer accordingly. - Now, we know that

p32is pointing to the 32-bit word containing our target-bitp32, so we find the target-bit, by usingTrailingZeroCount()and right shifting in a loop until we find the target bit’s position within the word, finally returning the offset when we’re done.

Let’s take a look at how this version fairs:

| Method | N | Mean (ns) | Scaled to “Naive” |

|---|---|---|---|

| NoIntrisics | 1 | 5.247 | 4.19 |

| NoIntrisics | 4 | 43.919 | 0.79 |

| NoIntrisics | 16 | 429.974 | 0.58 |

| NoIntrisics | 64 | 2,986.498 | 0.44 |

| NoIntrisics | 256 | 16,492.408 | 0.16 |

| NoIntrisics | 1024 | 112,049.075 | 0.06 |

| NoIntrisics | 4096 | 1,058,565.813 | 0.02 |

| NoIntrisics | 16384 | 13,714,191.734 | 0.010 |

| NoIntrisics | 65536 | 206,236,218.000 | 0.009 |

Quite an improvement already! To be fair, our starting point being so low helped a lot, but still an improvement. As a side note, this is, essentially, the code I’m running on our own bitmaps in production right now, since I don’t have intrinsics right now.

If there’s really one column where our focus should gravitate towards it’s the “Scaled” column on the right of the table. Each result here is scaled to its corresponding Naive version:

- For any bit length < 16, the old version runs faster, but marginally so, in absolute terms.

- Once we hit

N == 16and upwards, the landscape changes dramatically and our bit-twiddlingPopCount()starts paying off big-time: the speedup for 64 is already > 100% all the way up to 11100% speedup @ 64K.

CoreCLR & Architecture Dependent Intrinsics

Let us remind ourselves where things stand at the time of writing this post, when it comes to using intrinsics in CoreCLR:

- .NET Core 2.1 was released on May 30th 2018, with Intrinsics released as a “preview” feature:

- The 2.1 JIT kind of knows how to handle some intrinsics.

- To actually use them, we need to use the dotnet-core myget feed and install an experimental nuget package that provides the API surface for the intrinsics.

- No commitments were made that things would be stable/working.

- .NET Core 3.0 is the official (so far?) target release for intrinsics support in .NET Core:

- Considerably more intrinsics are supported than what was available with 2.1.

- No extra nuget package is required (intrinsics are part of the SDK).

- Work is still being very actively done to add more intrinsics and improve the quality of what is already there.

As we require intrinsics that were not available with 2.1, The code in repo is targeting a pre-alpha1 version of .NET Core 3.0 (i.e. netcoreapp3.0).

For people wanting to run this code, it’s relatively easy to do so, and non-destructive to your current setup:

-

Go to the Installers and Binaries section of the core-sdk project.

-

The left most column contains .NET Core Master branch builds (3.0.x Runtime).

-

Download the appropriate installer in

.zip/.tar.gzform: I used the linux one, but the windows / osx ones should be just as good. -

unzip/untar the installer somewhere (*Nix users beware: Microsoft does this entirely inhumane thing of packaging the contents of their distribution as the top level of

.tar.gz, so be sure tomkdir dotnet; tar -C dotnet xf /path/to/where/you/downloaded/the/tar.gzto avoid heart-ache). -

Adjust your

PATHenv. to find thedotnetexecutable in the new folder you just unzipped to, before anywhere else. (I did this locally in my terminal session). -

You should now be able to

dotnet restore|build|run|testthe BitGoo project(s). -

Just to be on the safe side, here is what

dotnet --infoprints for me:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

.NET Core SDK (reflecting any global.json): Version: 3.0.100-alpha1-20180720-2 Commit: 82bd85d0a9 Runtime Environment: OS Name: ubuntu OS Version: 18.04 OS Platform: Linux RID: ubuntu.18.04-x64 ... # No one really cares that much

Using POPCNT & TZCNT

The next step will be to replace our bit-twiddling PopCount() code with the PopCount() intrinsic provided by System.Runtime.Intrinsics.X86.Popcnt class in the 3.0 BCL, which should be replaced by a single CPU POPCNT instruction by the JIT at runtime.

In addition, we will also use the BMI1 (Bit Manipulation Intrinsics 1) TrailingZeroCount() intrinsic which maps to the TZCNT instruction.

These instructions do exactly what our previous hand written implementation did, except it’s done with dedicated circuitry in our CPUs, takes up less instructions in the instruction stream, runs faster and can be parallelized internally inside the processor.

I was very careful in the last post / code-sample, to use the exact same function name(s) as the intrinsics provided by the 3.0 BCL, so really, the code change comes down to mostly adjusting the two top using static statements:

1

2

3

4

using static System.Runtime.Intrinsics.X86.Popcnt;

using static System.Runtime.Intrinsics.X86.Bmi1;

// Rest of the code is the same...

That’s it! We’re using intrinsics, all done!

If you are having a hard time trusting me, here’s a link to the complete code.

Here are the results, this time scaled to the NoIntrinsics() version:

| Method | N | Mean (ns) | Scaled to “NoIntrinsics”` |

|---|---|---|---|

| POPCNTAndBMI1 | 1 | 2.358 | 0.44 |

| POPCNTAndBMI1 | 4 | 15.318 | 0.35 |

| POPCNTAndBMI1 | 16 | 128.712 | 0.31 |

| POPCNTAndBMI1 | 64 | 916.033 | 0.27 |

| POPCNTAndBMI1 | 256 | 5,005.190 | 0.30 |

| POPCNTAndBMI1 | 1024 | 44,606.327 | 0.39 |

| POPCNTAndBMI1 | 4096 | 408,871.712 | 0.39 |

| POPCNTAndBMI1 | 16384 | 5,205,533.285 | 0.39 |

| POPCNTAndBMI1 | 65536 | 76,186,499.286 | 0.37 |

OK, now we’re talking…

There can be no doubt that we have SOMETHING working: we can see a very substantial improvement across the board for every value of N!.

There are some weird things still happening here that I cannot fully explain yet at this stage, namely: how the scaling becomes relatively worse as N increases, but there is little to generally complain about.

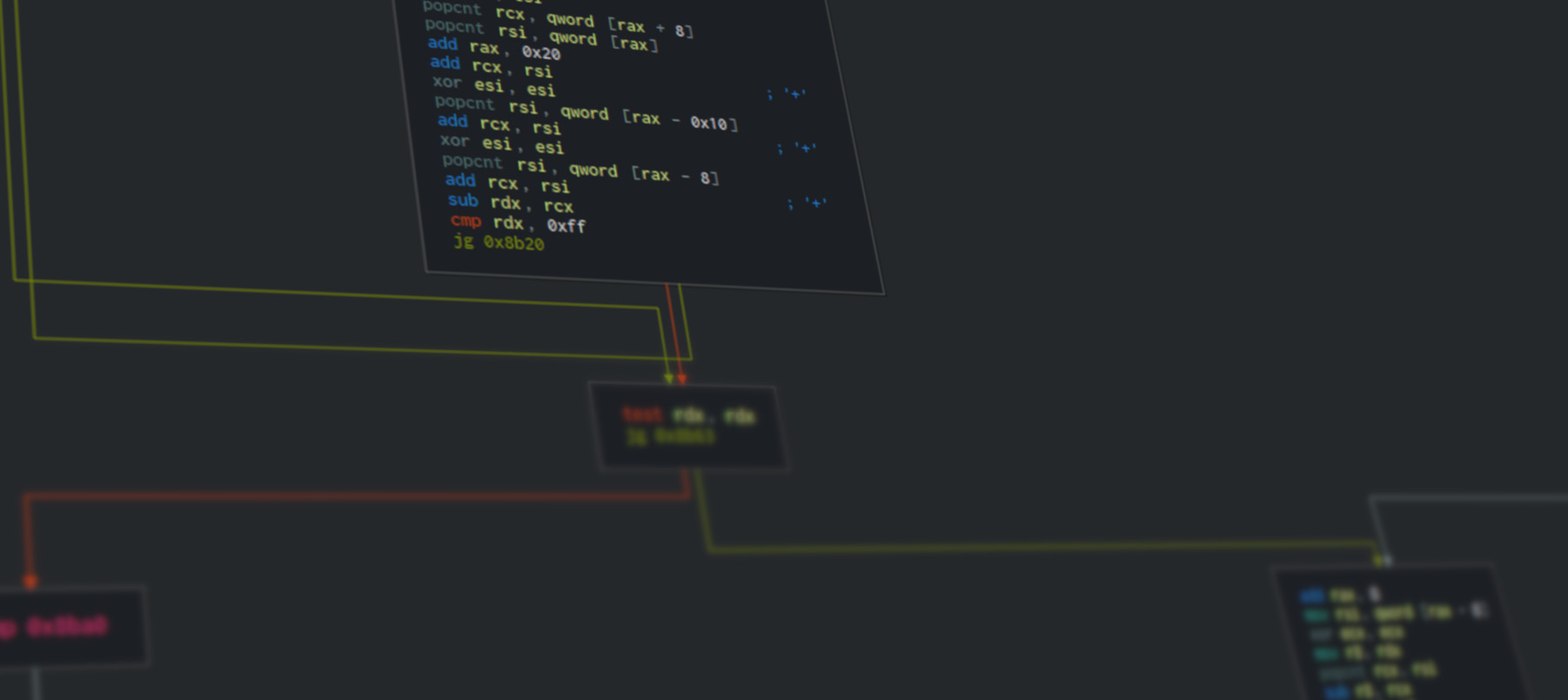

For those with a need to see assembly code to feel convinced, I’ve uploaded JITDumps to a gist, where you can clearly see the various POPCNT / LZCNT instructions throughout the ASM code (scroll to the end of the dump…).

What’s Next?

We’ve reached pretty far, and I hope it was interesting even if a bit introductory.

In the next post, we’ll continue iterating on this task, introducing new intrinsics in the process, and encounter some “interesting” quirks.

If you feel like you’re up for it, the next post is here…

-

Worry not, I reported and opened an issue on CoreCLR^1 before even starting to write this post and plan to do a deep-dive into this on the 3rd post ↩

-

Since our bitmap is filled with roughly 50%

0/1values, searching for 64K lit bits means going over roughly 128K bits, as an example. ↩ -

The TrailingZeroCount() method I’ve used here is the fastest, from independent testing, for C#. There are others but they either depend on having a compiler that can use CMOV instructions (which CoreCLR doesn’t yet), or on using LUTs (Look Up Tables) which I dislike since they tend to win benchmarks while losing in bigger scope of where the code is used, so I have a semi-religious bias against them. ↩