.NET Core 3.0 Intrinsics in Real Life - (Part 3/3)

As I’ve described in part 1 & part 2 of this series, I’ve recently overhauled an internal data structure we use at Work® to start using platform dependent intrinsics.

If you’ve not read the previous posts, I suggest you do so, as a lot of what is discussed here relies on the code and issues presented there…

As a reminder, this series is made in 3 parts:

- The data-structure/operation that we’ll optimize and basic usage of intrinsics.

- Using intrinsics more effectively

- The C++ version(s) of the corresponding C# code, and what I learned from them (this post).

All of the code (C# & C++) is published under the bitgoo github repo.

C++ vs. C#

I think I’ve mentioned this somewhere before: I started working on better versions of my bitmap search function way before CoreCLR intrinsics were even imagined. This led me to start to tinkering with C++ code where I tried out most of my ideas. When CoreCLR 3.0 became real enough, I ported the C++ code back to C# (which surprisingly consisted of a couple of search and replace operations, no more…).

As such, having two close implementations begs performing a head-to-head comparison.

After some additional work, I had basic google benchmark and google test suites up and running1

I’ll cut right to the chase and present a relative comparison between C++ and C# for the last version we ran in our previous post, The C# method is POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled and the C++ one is POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled2:

| Method | N | C# Mean (ns) | C++ Mean (ns) | C++/C# Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled | 1 | 2.249 | 3.338 | 148.42% |

| POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled | 4 | 10.904 | 11.037 | 101.22% |

| POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled | 16 | 50.368 | 43.786 | 86.93% |

| POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled | 64 | 208.272 | 202.366 | 97.16% |

| POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled | 256 | 1,580.026 | 1,493.020 | 94.49% |

| POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled | 1024 | 21,282.905 | 11,520.900 | 54.13% |

| POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled | 4096 | 255,186.977 | 133,976.543 | 52.50% |

| POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled | 16384 | 3,730,420.068 | 1,754,421.485 | 47.03% |

| POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled | 65536 | 56,939,817.593 | 26,613,731.568 | 46.74% |

There are a few things that stand out from this comparison:

- The percentage differences in the low bit counts (1,4) should be ignored, they are minuscule in absolute terms and within the margin of error.

- C# is doing pretty well up to 256 bits when we don’t execute the unrolled loop, it’s basically neck to neck with C++.

- Sweet mercy, what is going on with 1024 bits an onwards, inside the unrolled loop? Why is there such a big difference for what is a relatively optimized (and equivalent) piece of code between the two languages?

I’ll cut to the chase and answer this last question directly, then, proceed to explain the underlying relevant basics (tl;dr: it’s not so basic) of CPU pipelining and register renaming in order for the explanation to stick for people reading this that are not familiar with those terms/concepts.

The bottom line is: there is a bug in the CPU! There is a well known (even if very cryptic) erratum about this bug, and compiler developers are more or less generally aware of this issue and have been working around it for the better part of the last 5 years.

False Dependencies

So what is this mysterious CPU bug all about? The JIT was producing what should be, according to the processor documentation, pretty good code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

BEGIN_POPCNT_UROLLED_LOOP:

popcnt rsi, qword ptr [rcx]

sub rdx, esi

popcnt rsi, qword ptr [rcx+8]

sub rdx, esi

popcnt rsi, qword ptr [rcx+16]

sub rdx, esi

popcnt rsi, qword ptr [rcx+24]

sub rdx, esi

add rcx, 32

cmp rdx, 256

jge SHORT BEGIN_POPCNT_UROLLED_LOOP

What we see above is an excerpt from POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled method’s assembly code, and more specifically the unrolled loop that does 4 POPCNT instructions in succession.

Even if you are not an assembly guru, it’s pretty clear we have 4 pairs of POPCNT + SUB instructions, where:

- Each

POPCNTinstruction is reading from successive memory addresses and writing their result temporarily into a register namedrsi. - This temporary value is then subtracted using

SUBfrom another register which represents our good old C# variablen(the target-bit count).

The high-level explanation of the bug goes like this:

- The CPU should have detected that each

POPCNT+SUBinstruction pair is effectively independent of the previous pair (inside our unrolled loop and between the loop’s iterations). In other words: although all 4 pairs are using the same destination register (rsi), each such pair is really not dependent on the previous value ofrsi. - This dependency analysis, performed by the CPU, should have enabled it to use an internal optimization called register-renaming (more on that later).

- Had register renaming been triggered the CPU could have processed our

POPCNTinstructions with a higher degree of parallelism: In other words, our CPU, would run a fewPOPCNTinstructions in parallel at any given moment. This would lead to better perf or better IPC (Instruction-Per-Cycle ratio). - In reality, the bug is causing the CPU to delay the processing of each such pair of instructions for a few cycles, per pair, introducing a lot of “garbage time” inside the CPU, where it’s stalling, doing less work than it should, leading to the slowdown we are seeing.

Terminology wise, this sort of bug is called a false-dependency bug: In our case, the CPU wrongfully introduces a dependency between the different POPCNT instructions on their destination register, it thinks each POPCNT instruction is not only writing into rsi but also reading from it! (it does no such thing)

Given that this false dependency now exists, it is preventing the CPU from using register-renaming to execute the code more efficiently.

I will first focus on describing how compilers have been working around this, and afterward, I will describe in much more detail how the CPU employs register renaming to improve the throughput of the pipeline when the bug does not exist or is worked around.

Working Around False Dependencies

As I’ve mentioned, this bug has been around for quite some time: It was reported somewhere in 2014 and is unfortunately still persistent to this day on most Intel CPUs, at least when it comes to the POPCNT instruction2.

Luckily, compiler developers have been able to work around this issue with relative ease by generating extra code that breaks the aforementioned false-dependency. As far as I can tell, the people who originally wrote the workarounds were Intel developers, so they had a very good understanding of the exact nature of this false-dependency. What they opted to do was make compilers introduce a single-byte instruction that clears the lower 32-bits of the destination register. In our case, this comes in the form of a xor esi, esi instruction. This is the shortest way (instruction length-wise) in x86 CPUs to zero out a register. This instruction is a well known special case in the CPU since it “knows” the future value of the destination register (0) even without executing it, or knowing what its original value ever was. It appears the Intel engineers knew that the dependency is not the entire 64-bit register (rsi) but only on the lower 32-bit part of that register (esi3) and took advantage of this understanding to introduce a single byte fix into the instruction stream, which is relatively very cheap.

The correct x86 assembly, generated by a fixed JIT or compiler should look like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

BEGIN_POPCNT_UROLLED_LOOP:

xor esi, esi ; This breaks the dependency

popcnt rsi, qword ptr [rcx]

sub rdx, esi

xor esi, esi ; This breaks the dependency

popcnt rsi, qword ptr [rcx+8]

sub rdx, esi

xor esi, esi ; This breaks the dependency

popcnt rsi, qword ptr [rcx+16]

sub rdx, esi

xor esi, esi ; This breaks the dependency

popcnt rsi, qword ptr [rcx+24]

sub rdx, esi

add rcx, 32

cmp rdx, 256

jge SHORT BEGIN_POPCNT_UROLLED_LOOP

This short piece of code is the sort of code that gcc/clang would generate for POPCNT to work-around the bug. When read out of context, it looks silly… it appears like the compiler generated useless code, to begin with, and you’ll find people wondering about this publicly in stackoverflow and other forums from time to time, or worse yet: trying to “fix” it. But for most in-production x86 CPUs (e.g. all the ones that suffer from this false-dependency) this code will substantially outperform the original code we saw above…

Update: CoreCLR does the right thing

I originally started writing part 3 after I found this issue with the JIT, and submitting an issue, thinking I would finish writing this post before anyone would fix the underlying issue. I was wrong on both counts: Writing this post became an ever-growing challenge as I attempted to explain pipelines and register-renaming for the uninitiated (below), while Fei Peng fixed the issue in a matter of two weeks (Thanks!).

What CoreCLR now does (since commit 6957b4f) is always introduce the xor dest, dest workaround/dependency breaker for the 3 affected instructions LZCNT, TZCNT, POPCNT. This is not the optimal solution since the JIT will introduce this both for CPUs afflicted with this bug (specific Intel CPUs) as well as CPUs that don’t have this bug (All AMD CPUs and newer Intel CPUs).

From the discussion, it’s clear that this path was chosen for simplicity’s sake: it would require more infrastructure both to detect the correct CPU family inside the JIT, and introduce questions around what should the JIT do in case of AOT (Ahead Of Time) compilation, as well as require more testing infrastructure than what is currently in place on the one hand, while the one byte fix is very cheap even for CPUs that are not affected.

Let’s see if this CoreCLR fix does anything to our unmodified piece of code…:

| Method | N | Mean (ns) | Scaled To “buggy” CoreCLR | Scaled to C++ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled | 1 | 2.170 | 0.96 | 0.65 |

| POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled | 4 | 11.910 | 1.09 | 1.08 |

| POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled | 16 | 55.016 | 1.09 | 1.26 |

| POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled | 64 | 225.156 | 1.08 | 1.11 |

| POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled | 256 | 1,637.336 | 1.04 | 1.10 |

| POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled | 1024 | 11,698.421 | 0.55 | 1.02 |

| POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled | 4096 | 149,247.146 | 0.58 | 1.11 |

| POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled | 16384 | 1,904,945.748 | 0.51 | 1.09 |

| POPCNTAndBMI2Unrolled | 65536 | 27,712,720.427 | 0.49 | 1.04 |

It sure does! It appears now that the unrolled version is running roughly 85-101% faster for higher bit counts than it did with the previous, unfixed CoreCLR!. When compared to C++, performance is now pretty close and consistent for the important parts of the benchmark. If you consider, for a moment, that we got here by making the JIT spill out an extra, supposedly useless instruction, this makes the achievement that much more impressive :), as before, here is the JITDump with the newly fixed JIT in place.

Now, we can really see just how much of a profound effect this false-dependency had on performance. In theory, this might be the right time to finish this post, however, I couldn’t let it go without attempting to explain the underlying CPU internals of how and why the false-dependency had such a deep effect on performance. For readers well aware of how CPU pipelines operate and how they interact with the register renaming functionality on a modern super-scalar out-of-order CPU this is a good time to stop reading.

What follows is me trying to explain how the CPU tries to handle loops of code effectively, and how register renaming plays an important role in that.

The love/hate story that is tight loops in CPUs

It takes very little imagination to realize that CPUs spend a lot their processing time executing loops (or the same machine code multiple times, in this context).

We need to remember that CPUs achieve remarkable throughput (e.g. instructions per cycles, or IPC) even though the table, in some ways, is set against them:

- A modern CPU will often have a dozen or so stages in their pipeline (examples: 14 in Skylake, 19 in AMD Ryzen)

- This means a single instruction will take about 14 cycles on my cpu from start to finish if we were only executing that instruction and waiting for it to complete!

- The CPU attempts to handle multiple instructions in different stages of the pipeline, but it may become stalled (i.e. do no work) when it needs to wait for a previous instruction to advance through the pipeline enough to have its result ready (this is generally referred to as instruction dependencies).

- To improve the utilization of CPU caches (L1/2/3 caches) and memory bus utilization, most modern processors artificially limit the number of register names they support for instructions (seems like in 2018 everyone has settled on 16 general purpose registers, except for PowerPC at 32)

- That way instructions take up fewer bits and can be read more quickly over these highly subscribed resources (caches and memory bus).

- The flip side of this design decision is that compilers do not have the ability to generate code that uses many different registers, which in turn leads them to generate more code fragments that are dependent of each other because of the limited register names available for them.

With that in mind, let’s take the same, short piece of assembly code, which was generated by the JIT for our last unrolled attempt at, and see how it theoretically executes on a Skylake CPU.

Visualizing our loop

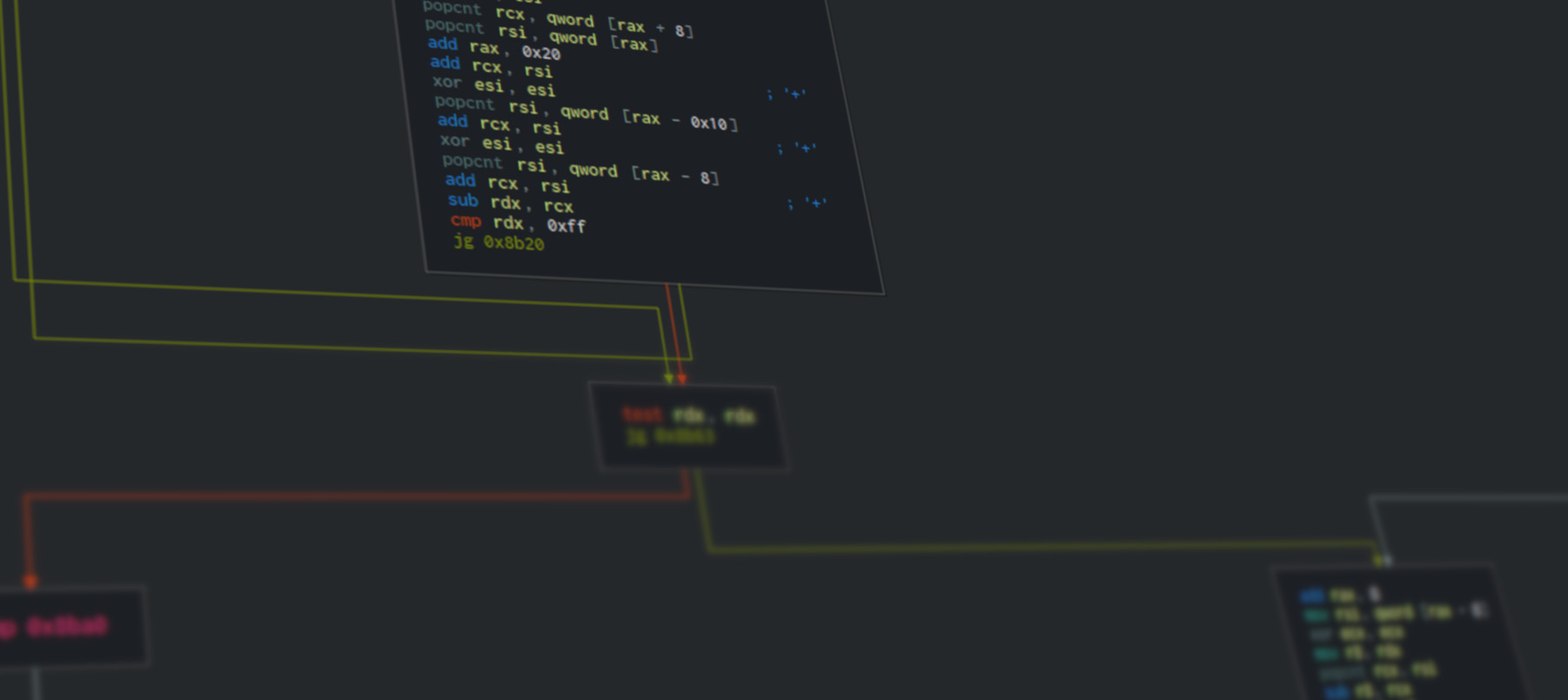

Without any additional fanfare, lets introduce the following visualization:

I created this diagram by prettifying a trace file generated by a little known tool made by Intel called IACA, which stands for Intel Architecture Code Analyzer. IACA takes a piece of machine code + target CPU family and produces a textual trace file that can help us see better what the CPU does, at every cycle of a relatively short loop.

If you dislike having to use commercial (non-OSS) tools, please note that there is a similar tool by the LLVM project called llvm-mca, and you can even use it from the infamous compiler-explorer.

Let’s try to break this diagram down:

- The leftmost column contains the loop counter, I’ve limited the trace to 2 [0, 1] iterations of that loop, to keep everything compact.

- Next, the instruction counter within its respective loop. Clearly we have 11 instructions per loop.

- Next, the disassembly, where we can see 4

POPCNTinstructions and they are interleaved with 4 subtractions of eachPOPCNTresult from the registerrdx - Next we see how the instructions are broken down to µops4:

For now, we will simply make note that everyPOPCNTwe have , having been encoded as an instruction that reads from memory AND calculates the population count, was broken down to two µops:- A load µop (

TYPE_LOAD) loading the data from its respective pointer. - An operation µop (

TYPE_OP) performing the actualPOPCNTing into our destination register (rsi).

- A load µop (

- Then comes the real kicker: IACA simulates what a Skylake CPU (specifically) should be doing at every cycle of those two loop iterations and provides us with critical insight into the state that each instruction is at every cycle (relative to the beginning of the first loop). These states are described by the coded symbols in each box, which I will shortly describe in more detail.

It is important to note that IACA, while being Intel’s own tool is not aware of the Intel CPU bug I just described. It is simulating what that processor should have done with NO false dependency…

While all the various states of the instruction within the pipeline are interesting I will give some more meaning to specific states:

| mnemonic | Meaning |

|---|---|

| d | Dispatched to execution: The CPU has completed decoding and waiting for the instruction’s dependencies to be ready. Execution will begin in the next cycle |

| e | Executing: The instruction is being executed, often in multiple cycles within a specific execution port (unit) inside the CPU |

| w | Writeback: The instruction’s result is being written back to a register in the register-file (more on this below), where it will be available for other instructions that might have a dependency on that instruction |

| R | Retired: The temporary register used during the execution/writeback has to be written back to the “real” destination register, according to the original order of the program code, this is called retirement, after which the CPUs internal, temporary register is free again (more on this below) |

I encourage you to try to follow this execution trace for a couple of instructions. I like to stare at these things for hours, trying to tell a story in my own head in the form of “what is the CPU thinking now” for each and every cycle. There is much we could say about this, but I will highlight a few remarkable things:

- I’ve highlighted the

Rsymbol/stage with a red-ellipse. For our purposes here, this represents the final stage of each instruction. To me, it’s very impressive to see how all of these instructions terminate execution either 0 or 1 cycles apart of each other. - By the time the first instruction (

POPCNT) reaches theR(retired) state at cycle 14, when it’s done, we are already executing, in some pipeline stage or another, all instructions from the next 4 iterations of this unrolled loop (I’ve limited the visualization to only 2 iterations for brevity, but you get the hang of it).- The processor is already (speculatively) executing loads from memory to satisfy our

POPCNTinstructions in loop iterations 1,2,3 before the first iteration has even completed running, and without even knowing for sure our loop would actually execute for that amount of iterations. - Quantitatively speaking: We have roughly 4 iterations of an 11 instruction loop (> 40 instructions) all running in parallel inside one core(!) of our processor. This is possible both because of the length of the pipeline (14 stages for this specific processor) and the fact that internally, the processor has multiple units or ports capable of running various instructions in parallel. This is often referred to as a super-scalar CPU.

- The processor is already (speculatively) executing loads from memory to satisfy our

In case you are interested in digging much more deeper than I can afford to go into this within this post, I suggest you read Modern Microprocessors: A 90-Minute Guide! to get more detailed information about pipelines, super-scalar CPUs, everything I try to cover here, and more.

For this post, I will focus on one key aspect that lies in the root of how the CPU manages to do so many things at the same time: register renaming.

Instruction Dependencies

Let’s look at the code again, this time adding arrows between the various instructions, marking their interdependencies.

If we interpret this code naively (and wrongly), we see that rsi is being used in each and every instruction of this code fragment, this could lead us to assume that the heavy usage of rsi is generating a long dependency chain:

- The

POPCNTis writing intorsi. rsiis then used as a source for the subtraction fromrdx, so naturally, thesubinstruction cannot proceed beforersihas the value ofPOPCNT.- The next

POPCNTis again writing torsibut would seemingly be unable to write before the previoussubhas finished. - After four such operations, we loop (in turquoise) again and we are again taking a dependency on

rsiat the beginning of the loop.

This naive dependency analysis pretty much contradicts the output we saw come out of IACA in the previous diagram without further explanation. It would seem impossible for the CPU to run so many things in parallel where every instruction here seems to have a dependency through the use of the rsi register.

Moreover, both our original C# and C++ code did not force the JIT/compiler to re-use the same register over and over. It could have allocated 4 different registers and used them to generate code where each POPCNT + SUB pair would be independent of the previous one, so why didn’t it do so?

Well, it turns out there is no need to! The JIT/compiler is doing exactly what it needs to be doing, it is just us, that need to learn about a very important concept in modern processors called register renaming.

Register Renaming

To understand why anyone would need something like register renaming, we first need to understand that CPU designers are stuck between a rock and a hard place:

- On one hand they want to be able to read our program code as fast as possible, from memory 🡒 cache 🡒 instruction decoder (a.k.a CPU front end), this requirement leads down a path where they have to severely limit the number of register names available for machine code, since fewer register names leads to more compact instructions (fewer bits) in memory and more efficient utilization of memory buses and caches.

- On the other hand, they would like to give compilers / JIT engines as much flexibility as possible in using as many registers as they want (possibly hundreds) without needing to move their contents into memory (or more realistically: CPU cache) just because they ran out of registers names.

These contradicting requirements led CPU designers to decouple the idea of register names and register storage: modern CPUs have many more (hundreds) or physical registers (storage) in their register-file than they have names for our software to use. This is where register renaming enters the scene.

What CPU designers have been doing, for quite a long time now (before 1967, believe it or not!) is really remarkable: they have been employing a really neat trick that effectively gets the best of both worlds (i.e. satisfy both requirements) at the cost of more complexity, more power usage, and more stages in the pipeline (hence also a little slowdown in the execution of a single instruction) to achieve better pipeline utilization at the global scale.

This optimization, named “Register renaming”, accomplishes just that: by analyzing when a register is being written (write-only, not read-write) to, the CPU “understands” that the previous value of that register is no longer required for the execution of instructions reading/writing to that same register from that moment onwards, even if previous instructions have not completed (or started) execution! What this really means, is that if we go back to the naive (now you see why) dependency analysis we did in the previous section, it’s clear that each POPCNT + SUB pair are actually completely independent of each other because they begin with overwriting rsi! In other words, each POPCNT having written to rsi is considered to be breaking the dependency chain from that moment onwards.

What the CPU does, therefore, is continuously re-map named registers to different register locations on the register-file, according to the real dependency chain, and use that newly allocated location within the register file (hence the initial “Allocation” stage at the IACA diagram above) until the dependency chain is broken again (e.g. the same register is written to again).

I cannot emphasize how important of a tool this is for the CPU. Register renaming allows it to schedule multiple instructions to execute concurrently, either at different stages of the same pipeline or in parallel in different execution ports (pipelines) that exist in a super-scalar CPU. Moreover, this optimization achieves this while keeping the machine code small and easy to decode, since there are very few bits allocated for register names!

How big of a deal is this? How good is the CPU in using this renaming trick? To best answer this from a practical standpoint, I think, we can take a look into the disparity between how many register names exist, for example, in the x64 architecture, that number being 16, and how many physical register storage space there is on the register-file, for example, on an Intel Skylake CPU: 180 (!).

After the temporary (renamed) register has finished its job for a given instruction chain, we are still, unfortunately, not entirely done with it. Understand, that the CPU cannot look too far into the incoming instruction stream (mostly a few dozen bytes), and it can not know, with certainty, if the last written value it just wrote to a renamed register will not be required by some future part of the code it hasn’t seen yet, hundreds of instructions in the future. This brings us to the last phase of register renaming, which is retirement: The CPU must still write the last value for our symbolic register (rsi) back to the canonical location of that register (a.k.a the “real” register), in case future instructions that have not been loaded/decoded will attempt to read that value.

Moreover, this retirement phase must be performed exactly in program order for the program to continue operating as its original intention was.

Wrapping up: clearing the register for the rescue

So going back to our false-dependency bug, we can now hopefully understand the underlying issue and the fix armed with our new knowledge:

Our Intel CPU wrongly misunderstands our POPCNT instruction, when it comes to its dependency analysis: It “thinks” our usage of rsi is not only writing to it but also reading from it.

This is the false-dependency at the root of this issue. We cannot see this with IACA, but we can understand it conceptually: If the CPU (wrongfully) “thinks” that our second POPCNT has to READ the previous rsi value, then no register renaming can occur at that point, and the second POPCNT instruction cannot execute in parallel to the first one, it needs to wait for the completion of the first POPCNT and basically stall for a few precious cycles, in order for the previous rsi to be written back somewhere. Naturally this is true for every unrolled POPCNT in our loop and also between loop iterations.

This alone is enough to cause the perf drop we saw originally with the C# code before CoreCLR was patched. Once the xor esi,esi dependency breaker is added to the instruction stream, we are basically “informing” the CPU that we really are not dependent on the previous value of rsi and we allow it to perform register renaming from that point onwards. It still wrongfully thinks that POPCNT reads from rsi but thanks to our otherwise seemingly superfluous xor, this is an already renamed rsi and the pipeline stall is averted.

I think it is pretty clear by now, although we barely scratched the surface of CPU internals, that CPUs are very complex, and that in the race to extract more performance out of code, today’s out-of-order, super-scalar CPUs go into extreme lengths to find ways to parallelize machine code execution.

It should be also clear that it’s important to be able to empathize with the machine and understand the true nature of its inner workings to really be able to deal the weirdness we experience as we try to make stuff go faster.

It would be great if all we needed to do was keep compiler and hardware developers well fed and well paid so we could do our job without needing to know any of this, and to a great extent, this statement is true. But more often than not, extreme performance requires deeper understanding.

-

As a side note, after not doing serious C++ work for years, coming back to it and discovering sanitizers, cmake, google test & benchmark was a very pleasant surprise. I distinctly remember the surprise of writing C++ and not having violent murderous thoughts at the same time. ↩

-

Apparently Intel has fixed the bug (according to reports) for the

LZCNTandTZCNTinstructions on Skylake processors, but not so for thePOPCNTinstruction for reasons unknown to practically anyone. ↩ -

yes, x86 registers are weird in that way, where some 64 bit registers have additional symbolic names referring to their lower 32, 16, and both 8 bit parts of their lower 16 bits, don’t ask. ↩

-

µop or micro-op, is a low-level hardware operation. The CPU Front-End is responsible for reading the x86 machine code and decoding them into one or more µops. ↩